My name is Tamlin, this summer, as part of my MSc studies at the University of York, I took part in a placement with the Maldives Whale Shark Research Program. Having been fascinated by sharks since I was young, the opportunity to contribute to current whale shark research was a chance I had to take. My placement formed my final thesis with the aim of ‘Assessing the environmental and biological variables that make South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area (SAMPA) a world renowned whale shark aggregation site’.

During my placement I lived in Dhigurah in the South Ari Atoll, a place where the ocean is alive with whales, sharks, dolphins, turtles, and flying fish, put simply, a budding marine biologist’s delight. The following is a daily extract from my time spent on placement with the Maldives Whale Shark Research Program (MWSRP) on Dhigurah, the Maldives.

‘The day is hot, after looking at the blue azure waters for the best part of three hours, frustration is beginning to build. I can see fish swimming in the depths, I can even see stingrays resting on the bottom, but what I can’t see is whale sharks, where are they? South Ari Atoll is one of the best places to see the largest living fish, so surely they can’t hide for too long. Then a shadow emerges into view, is it a rock? No it’s moving…slowly, could it be our elusive shark or is it just another drifting bin bag? No this is the moment, it’s shark o’clock, Shark! Shark! Shark! we shout and point our captain towards the largest shark in the sea. We race from the top deck, throw on our fins and jump into the Indian Ocean, masks and cameras ready. There he is, Fernando, the star of the show. At almost 7 meters he moves with an assurance and confidence, even when we swim up to him, spluttering, shrieking and thrashing our fins around excitedly. Fernando himself seems fairly oblivious to us, happy to simply saunter forward smoothly in the shallow reef waters, no doubt warming himself with the sun’s rays to prepare for another deep feeding dive. His spots seem to glow as he moves effortlessly into the current, his dermal denticles ensuring he slips slowly but seamlessly away from our desperate swimming. We try in vain to keep with him, but as he fades into the blue we are left with a feeling of amazement, bewilderment and just from the size of him, a serving of humble pie, what a creature! Tonight we’ll upload our photos to the Big Fish Network (BFN), using Fernando’s spots like a fingerprint to confirm his identity, although the scarring on his tail is a tell-tale sign it’s him. We raise our heads and realise it’s a long way back to the boat, so we kick our legs, scale the ladder and climb to the roof. The search for earth’s biggest elasmobranch begins again.’

‘The day is hot, after looking at the blue azure waters for the best part of three hours, frustration is beginning to build. I can see fish swimming in the depths, I can even see stingrays resting on the bottom, but what I can’t see is whale sharks, where are they? South Ari Atoll is one of the best places to see the largest living fish, so surely they can’t hide for too long. Then a shadow emerges into view, is it a rock? No it’s moving…slowly, could it be our elusive shark or is it just another drifting bin bag? No this is the moment, it’s shark o’clock, Shark! Shark! Shark! we shout and point our captain towards the largest shark in the sea. We race from the top deck, throw on our fins and jump into the Indian Ocean, masks and cameras ready. There he is, Fernando, the star of the show. At almost 7 meters he moves with an assurance and confidence, even when we swim up to him, spluttering, shrieking and thrashing our fins around excitedly. Fernando himself seems fairly oblivious to us, happy to simply saunter forward smoothly in the shallow reef waters, no doubt warming himself with the sun’s rays to prepare for another deep feeding dive. His spots seem to glow as he moves effortlessly into the current, his dermal denticles ensuring he slips slowly but seamlessly away from our desperate swimming. We try in vain to keep with him, but as he fades into the blue we are left with a feeling of amazement, bewilderment and just from the size of him, a serving of humble pie, what a creature! Tonight we’ll upload our photos to the Big Fish Network (BFN), using Fernando’s spots like a fingerprint to confirm his identity, although the scarring on his tail is a tell-tale sign it’s him. We raise our heads and realise it’s a long way back to the boat, so we kick our legs, scale the ladder and climb to the roof. The search for earth’s biggest elasmobranch begins again.’

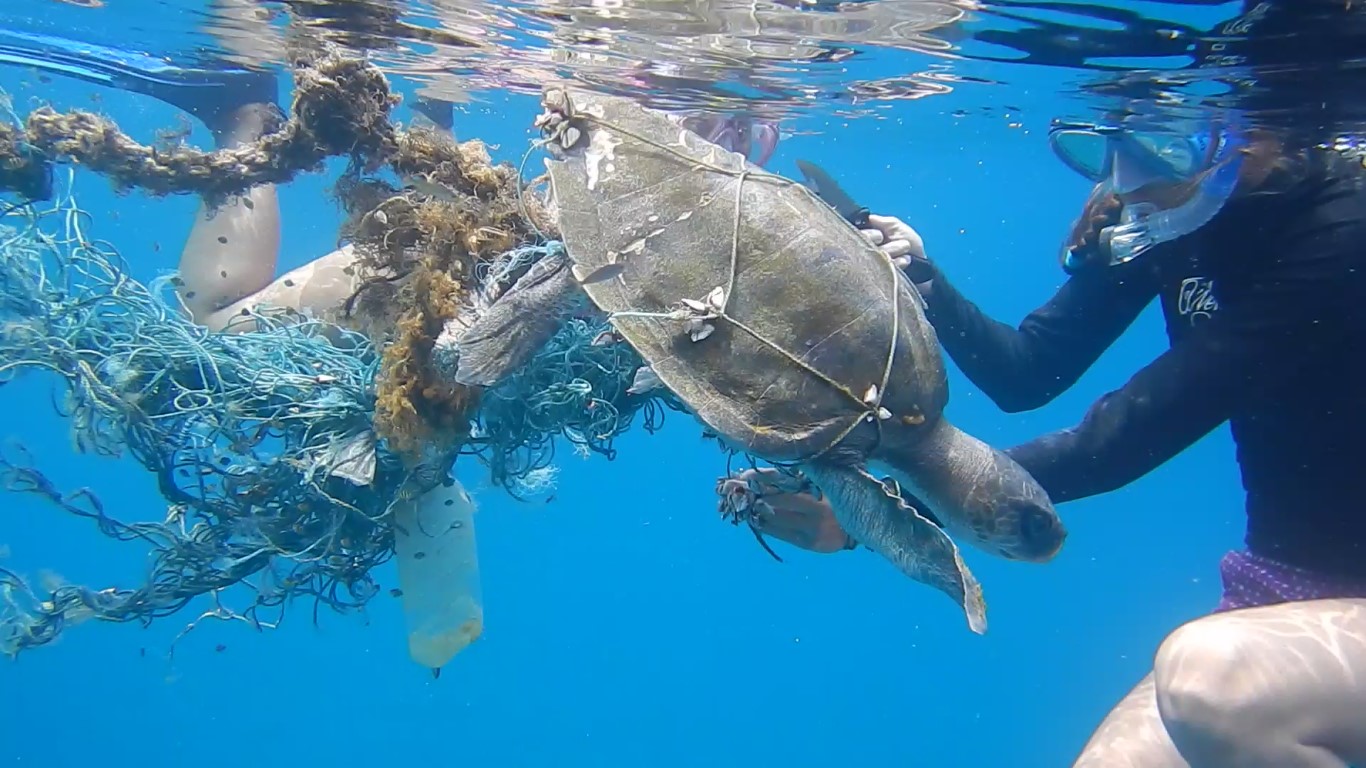

My placement entailed aiding the MWSRP with their volunteer programme and data collection in the field. I was lucky enough to encounter more than twenty-five whale sharks in all, and upload photos and environmental data to the growing MWSRP database. We spent each day at sea patrolling the South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area (SAMPA), looking for whale sharks, fishing vessels, megafauna and tourist excursion and dive boats. We recorded the number of tourists swimming with each whale shark, the number of boats present at each encounter, any injuries to each shark, and the presence of any other megafauna, as well as a host of environmental variables. We also removed ocean trash and ghost nets spotted within the MPA, giving some tangled animals a second chance.

My placement expanded my experience of working at sea, supervising volunteers, collecting accurate data and using scientific equipment. I also witnessed how a charity is run on the ground, and how important consistent, accurate data collection is to science, research and furthering our understanding of the marine world. It was invigorating to see so much life in the sea, in a world with so many species suffering population declines, South Ari Atoll felt like a harbour of ocean marine life. Additionally, when I was on placement the Discovery Channel came out to film what we were doing, I even made it onto Shark Week!

Upon returning home the real work began as I was tasked with solving a puzzle, writing my thesis and finding out why the whale sharks of South Ari Atoll are present all year round? To do this I analysed three years of environmental and biological data to find the variables driving whale shark encounters. I even downloaded sea surface temperature and chlorophyll a data from NASA satellites circling the globe to add additional data sources to my study.

The whale shark encounter and environmental data used in this study were collected by the MWSRP team from the 1st of January 2014 to the 18th of April 2017. Surveys were conducted from Dhigurah to Rangali along the epipelagic reef fringe in a local vessel. A mean of whale sharks per day (shark encounters/search effort) and 12 environmental variables were calculated to allow for accurate comparisons between data. Of these variables, chlorophyll a (P=0.0217) and current strength (P=0.0058) were found to have a significant relationship with mean whale sharks per day (α=0.026).

From my findings I was able to deduce that the environmental and biological variables analysed affect the year round aggregation of whale sharks at SAMPA, but they are not the primary drivers of whale shark site fidelity. Although chlorophyll a may contribute to increased prey abundance, and was found to be significant in this study, it does not explain the consistent presence of whale sharks in the MPA.

My project will no doubt serve as a basis for further studies, and provides a sure sign that the reasons driving this ever present whale shark population are more complex than first thought. Perhaps they just like the Maldivian cuisine, or maybe the sunshine is particularly enjoyable? Whatever the reason, my project has helped advance our understanding by ruling out some of the environmental variables thought to drive aggregations, but the same question remains – why are they here? The whale shark mystery remains unsolved, could you solve it?