Things You Didn’t Know You Didn’t Know About Whale Sharks

As we come towards the end of an incredibly exciting year we thought it would be nice to share some our staffs’ favourite facts about whale sharks and why we love these massive fish so much!

- Every individual whale shark has a unique pattern of spots and stripes, similar to how humans are identifiable by their fingerprints.These markings make them easy to identify from photographs which, as well as being a non-invasive identification method, has the bonus of making them an ideal species for citizen science programmes. This helps us track their movements across the Maldives as they are highly mobile species!

- Whale sharks have teeth! One of the first questions we’re often asked when introducing the whale shark is ‘does it have teeth’? Most people ask this as part of an internal risk assessment they run through their mind when deciding if they really do want to hop into the water when someone shouts ‘SHARK’, and the answer is yes they do! but they are so small that they pose no threat to humans, we are not even certain what they do use them for!

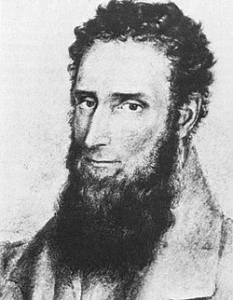

- A whale shark’s scientific name is Rhincodon typus. The whale shark was first described by the a Scottish, military surgeon, Andrew Smith, in the 19th century. He was a preeminent zoologist in South Africa at the time (several species now bear his name), as well as a pen pal of Charles

arwin! When a whale shark was harpooned off South Africa in Table Bay, 1928, Smith was on the scene to describe this new species to science. The question ‘does it have teeth?’ must have been on his mind, because after discovering hundreds of rows of barely visible teeth below its lips he chose to call this ocean giant, Rhincodon typus, which literally means rasp-tooth (Rhin = rasp codon = tooth). A few years later Smith would have his hand in suggesting a tooth themed name for another big shark: Carcharodon, or ‘ragged tooth’, is the species name of Carcharodon carcharias which is the great white shark.

arwin! When a whale shark was harpooned off South Africa in Table Bay, 1928, Smith was on the scene to describe this new species to science. The question ‘does it have teeth?’ must have been on his mind, because after discovering hundreds of rows of barely visible teeth below its lips he chose to call this ocean giant, Rhincodon typus, which literally means rasp-tooth (Rhin = rasp codon = tooth). A few years later Smith would have his hand in suggesting a tooth themed name for another big shark: Carcharodon, or ‘ragged tooth’, is the species name of Carcharodon carcharias which is the great white shark. - No-one ever, in history, has seen whale sharks mating! As biologists and conservationists, mating and breeding habits are one of the fundamental pieces of information needed for understanding the population growth or loss of whale sharks. The locations of where these behaviours take place are also just as important, as whale sharks are likely to be more venerable during this period and need greater protection. This is the biggest fish in the ocean and we have no idea when, where, how or how often they breed?! That much mystery just begs us to carry on our work!

- Everything we know about whale shark reproduction comes from ONE pregnant female that was caught in Taiwan in 1995! This female had over 300 embryos that were at all different stages of development! Genetic analysis of 30 of these embryos showed that they all had the same father, leading scientists to the conclusion that whale sharks can store sperm and fertilize eggs when ready. This mating strategy makes sense, as encounters with the opposite sex are likely few and far between in the open ocean.

- Whale sharks have the largest eardrum in the animal kingdom! No one really knows what whale sharks do hear but it is thought that this enormous organ helps them find their prey. Imagine being able to hear plankton!

- Whale shark behaviour varies between environments and individuals. Very little is known about the meaning of whale shark behaviour, however it is interesting to observe how the whale sharks we encounter can all behave differently in the presence of humans. There are those, such as Adam and Fernando, who are very accustomed to having people swimming with them (both seen over 200 times since 2006 and 2008 respectively!), and usually stay around for a while during an encounter before diving off the reef again; whilst other whale sharks show signs of evasive behaviour even when the code of conduct is followed (no flash photography used, no obstruction, no touching and maintaining a 4 m distance from the shark). At the other end of the scale, whale sharks that are new to the area and smaller in size can often be quite inquisitive, trying to approach humans and boats to, presumably, get a better look at them.