When I was a student in primary school we had arts and crafts several days a week.

My teacher would encourage us to use our imaginations and draw anything we wanted. At times I found it effortless to pick up a blank piece of paper and draw a picture. More often than not, though, I found the exercise difficult and would not be able to make a decision on what to draw. To help get over my mental block, the teacher would draw a squiggle or random shape on the paper.

With a constraint on the page, the anguish that came from staring at a blank void vanished. A curved line became the bow of a ship or the tail of a cat. Turn the paper in another direction and I could see a fire-breathing dragon soaring over the clouds. Instead of being a barrier or a limit to creativity, the shape would act as a kickstarter for my imagination. In essence, the constraint would fuel greater creativity.

Fast-forward several decades to the present.

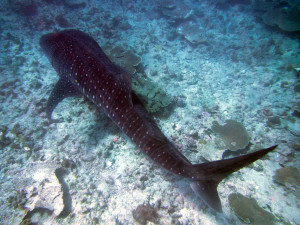

We are in the South Ari Atoll of the Maldives. The southern most 42-km2 fringe of coral reef happens to be one of the most significant places in the world to see whale sharks. The area, known as the South Ari Atoll Marine Protected Area (S.A. MPA), is arguably the best place to swim with the docile giants year-round. What makes the area so special to the country is that whale sharks can be encountered swimming (relatively) slowly in very shallow water. This phenomenon, combined with stunning vistas of tropical islands, makes for an ideal setting to run whale shark snorkelling and diving excursions.

Each year snorkelers and divers visit the area by the tens of thousands hoping to get a glimpse of the magnificent creatures.

Yet the rising popularity also comes with it’s own challenges. From the surface of the water, the vessels in the MPA can resemble an armada, with boats of all shapes and sizes patrolling the shallow reef in search of a whale shark. Regardless of the Protected Area status, there are no regulations in place to guide operators. This results in boats and their excited guests inevitably ‘sharing’ a shark. It is not uncommon now for encounters to have over 100 guests from multiple boats all jockeying for positions to swim alongside the sharks. Not only can this be precarious for the tourists in the water due to the heightened presence of boat traffic and other swimmers, but it may also be a contributing factor that triggers evasive behaviour in the sharks.

WS151 ‘Nufail’ was injured by a boat, slicking the top half of his caudal (tail) fin off. It has scarred over and healed well.

The research highlights another alarming area. Nearly 67% of the whale sharks encountered in the S.A. MPA show evidence of injury as a result of colliding with boats. These incidences result in injuries to the sharks ranging from minor scraps to serious amputations and lacerations. Sadly, it is usually easier to identify individual whale sharks by their scars than by their spot patterns. While it may not be correct to assume that boats in the S.A. MPA are the point of impact, it is not farfetched to postulate that whale sharks run higher risks in areas they are known to aggregate at the surface where there is also heavy boat traffic.

The question remains, what happens if this continues?

WS044 ‘Idris’ made an appearance on November 17, 2013 – the first time since December of 2008. South Ari MPA is a healthy ecosystem that humans must steward.

Will we inevitably reach a tipping point where the sharks will not return? As with countless other species and environments, negative human impact is all too evident. In this case, whale sharks are getting seriously injured and human safety is called into question. With no regulation or management of the area the risk factor only increases. When will we make the commitment to do this better – when someone is accidently killed or when there are no sharks left to swim with? Do we really want to wait until it is too late to collectively decide to take action?

The constraints are clear – ensure the utmost safety for both humans and whale sharks so that our kids, and their kids, can experience the incredible feeling of swimming alongside the world’s largest fish. This is where we need to start. The page is not blank. The foundation has been laid; we just need to build on top of it. No one person or group can do this alone though.

Imagine what can be designed if we tap into our collective creativity.

We can truly harness the power of collaboration and cooperation and the S.A. MPA can be the example. It can be the golden rule of how to effectively, sustainability, ethically, and economically manage whale shark tourism. The upside is that if this can be done then it creates a positive feedback loop meaning that what is good for conservation is good for business. For this to happen all stakeholders – from government agencies, safari boats, and resorts to local communities and NGOs – must be included in the process. Together we can paint a brighter future.